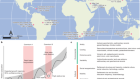

One in ten residents of China’s coastal cities could be living below sea level within a century, as a result of land subsidence and climate change, according to a paper published in Science today1.

Some 16% of the mapped area of China’s major cities is sinking “rapidly” — faster than 10 millimetres every year. An even greater area, roughly 45%, is sinking at a “moderate” rate, the paper says, meaning a downward trajectory of greater than 3 mm annually. Affected cities include the capital Beijing, as well as regional capitals, including Fuzhou, Hefei and Xi’an.

The situation could see one-quarter of China’s coastal lands slip below sea level within a few decades, posing “serious threats” to the hundreds of millions of people who live on the coast, the paper notes.

That sinking feeling

“Subsidence is certainly not only a problem in China. Many other parts of the world share the same problem,” says Ding Xiaoli, a geodesist at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Subsidence is when land sinks relative to sea level, usually owing to extraction of subsurface water, rock or other resources.

In the famously low-lying Netherlands, roughly one-quarter of the land has subsided to below sea level. And by 2040, almost one-fifth of the world’s population is projected to be living on sinking land.

Jakarta has become the most rapidly subsiding capital in the world, prompting Indonesia to propose a new capital city.

In the United States, more than 44,000 square kilometres of land across 45 states has been directly affected by subsidence, with more than 80% of the cases relating to groundwater extraction, often for agricultural purposes.

Ding says that the study provides an interesting snapshot of the situation in China, and crucially links the issue to the populations affected.

The authors, led by Tao Shengli, a researcher in remote-sensing technology at Peking University in Beijing, assessed 82 cities across China with a population of more than 2 million. They used radar pulses from satellites to measure the changes in the distance between the satellite and the ground to examine how its elevations changed between 2015 and 2022.

They found that the cities facing severe subsidence are concentrated in five regions, and cover both coastal and inland cities.

Also on the list are cities in the largely land-locked southwest, such as Kunming, Nanning and Guiyang — a finding that surprises Zhou Yuyu, a geographer at the University of Hong Kong. “These cities are not as densely populated or industrialized as some other parts of China, yet they still experience significant subsidence,” he says.

Losing ground

The paper links a range of natural and human factors to sinking, such as the depth of a city’s bedrock, groundwater depletion, the weight of buildings, the use of transport systems and underground mining.

Previous studies2 have found that excessive groundwater extraction is a key cause of severe land subsidence in cities across the world.

But there are also stories of successful mitigation. Tokyo slowed its sinking from a rapid 240 mm a year in the 1960s to about 10 mm a year in the early 2000s, after passing laws that limited groundwater pumping. Shanghai, China, which sank by a staggering 2.6 metres between 1921 and 1965, reduced its annual rate of sinking to about 5 mm after implementing a series of environmental regulations.

“The key to addressing China’s city subsidence could lie in the long-term, sustained control of groundwater extraction,” the paper says.

Ding says that, in cities such as Macao and Hong Kong where no groundwater is used, subsidence mainly comes from consolidation — downward movement as a result of soil being compressed — after land reclamation.

The authors also listed the weight of buildings as a factor. Contrary to expectations, heavier buildings, such as the skyscrapers in Shanghai, tend to sink slower than lighter structures do, possibly because those buildings are anchored on deeper rock, according to the paper.

Double whammy

As cities sink, global sea levels are also rising, owing to the effects of climate change. This double whammy will cause 22–26% of China’s coastal lands to drop below sea level by 2120, the paper says.

Wei Meng, a geophysicist at the Graduate School of Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island in Kingston regards the figures as “terrifying”.

In 2022, Wei and his colleagues found that land was sinking faster than sea levels were rising in many coastal cities worldwide. They predicted that these cities would be challenged by flooding “much sooner” than timelines projected by sea-level models if they continued to sink at current rates.

Climate change might exacerbate sinking in other ways, such as by affecting where and when it rains — or doesn’t rain.

“Increasing droughts can prompt excessive groundwater extraction, contributing to subsidence in urban areas,” Zhou says.

Dike systems could be a cost-efficient way to prevent inundation as cities’ elevations fall, the paper says.

The paper’s authors did not reply to Nature’s request for comment.

Tehran’s drastic sinking exposed by satellite data

Tehran’s drastic sinking exposed by satellite data

Floods: Holding back the tide

Floods: Holding back the tide